EXCISED HOMICIDES

Click below to put portraits in context.

1. Indiana lovers.

2. A man from Texas.

3. Two men from Georgia.

4. Unknown.

5. Three men and a boy from Nebraska.

6. A Florida girl.

Sanctioned by law and the public opinion of White people, race-based lynchings became more than a pattern of racial terrorism, they also assumed the vestige of a festival; an event celebrated by communities that centered on the main characteristic of that community – racism. Lynchings provided a sense of White belonging. a form of entertainment popular in rural communities. The perceived experience of racial superiority helped generate unity among White families.

The 1904 murders of Luther Holbert and his wife provide an example of the festive nature of lynchings:

“Suspected of killing a white plantation owner, Luther Holbert - a Black sharecropper - attempted to escape from his home in Vardaman's Mississippi with his wife before a lynch mob could dispense its own form of "justice." Catching up with the Holberts, the mob bound the couple to trees. While the mob's ringleaders forced the Holberts' to hold out their hands in order that their fingers could be chopped off one by one – an audience of 600 spectators enjoyed treats like deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey in a festive atmosphere. The Holberts' ears were amputated and those severed appendages, along with the disconnected digits, became prized souvenirs. Mr. Holbert was beaten severely enough so that his skull was fractured and one eye was left dangling from its socket. When someone in the crowd produced a large corkscrew, that instrument was used to alternately bore into husband and wife, each time gouging out "spirals...of raw, quivering flesh" when withdrawn. Finally, the tortured man and woman were burned alive.”

With the advent of the civil rights era, many communities attempted to excise the thousands of homicides that had taken place, at the same time promulgating myths about the happy Black slave, well-treated Latino farm worker, and friendly Asian servant who was “one of the family.”

But efforts to make lynchings invisible proved impossible, they had become a common, community based part of American life, well documented by picture-post cards, letters, photographs, and newspapers accounts.

Some men and women who were lynched were never identified, few have received the honor due them,[a] none of their killers have been prosecuted, and the full truth about many mass murders in the United States remain a mystery to this day.

[a] Equal Justice Initiative’s Community Remembrance Project. http://eji.org/reports/community-remembrance-project

L.A. COVER UP – THE CHINESE MASSACRE OF 1871

The “Chinese Massacre” took place on Calle de los Negros, also known as "Nigger Alley" (the alley later became part of Los Angeles Street). On October 24, 1871 approximately 20 Chinese residents of Los Angeles were systematically tortured and then hanged by a mob of Whites and Latinos. Women and children participated in the hangings while other rioters looted Chinese dwellings.

At first, the massacre received significant publicity; however, in the years that followed the facts surrounding the lynchings became invisible. Official histories of the City of Los Angeles ignored the event, and the names of the perpetrators and the dead all but disappeared from public records. Invisibility intensified because California law did not allow Chinese to testify in court. At the time, there was no legal redress for Chinese immigrants concerning civil wrongs or criminal acts against them.

Too many people were involved for all the guilty to be punished—or even accused. However, because of the courage of a lone prosecutor, ten rioters were charged with the murder of one man: Choe Long Tong.[a] Most of the defendants were over thirty years old and many were family men. Eight were found guilty of manslaughter:

Alvarado, Esteban

Austin, Charles

Botello, Refugio

Crenshaw, L. F.

Johnson, A. R.

Martinez, Jesus

McDonald, Patrick M.

Mendel, Louis

The California Supreme Court, in short decision remarkable for its lack of citations and obtuse reasoning, reversed the convictions. See, People v. Crenshaw, 46 Cal. 65 (1873). There was no retrial, nor any additional prosecutions. The murderers went free.

Recent efforts have attempted to bring some visibility to the Chinese Massacre. See: Johnson, John (10 March 2011), "How Los Angeles Covered Up the Massacre of 17 Chinese". LA Weekly; "Chinese Massacre of 1871". University of Southern California; Scott Zesch, The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871 (Oxford); and Wikipedia, Chinese Massacre of 1871. Despite these publications, facts about the perpetrators and the subsequent cover-up remain invisible, confusion continues about exactly how many Chinese were murdered, and many public statements about the event remain inaccurate.[b]

An interesting approach to rendering visible what was once excised was developed by artist Ken Gonzales Day in a project entitled Hang Trees: http://kengonzalesday.com/projects/hangtrees/walkingtour.htm. Thanks to his efforts, at least we now have an idea of the names (but not the full names) of some of the victims of the Chinese Massacre:

Ah Cut

Ah Long

Ah Te

Ah Wha

Ah Won

Chang Linn

Day Kee

Fong Won

Gene Tong or Chee Lung Tong

Ho Hing

Leong Quai

Lo Hi

Wau Foo

Wong Chin

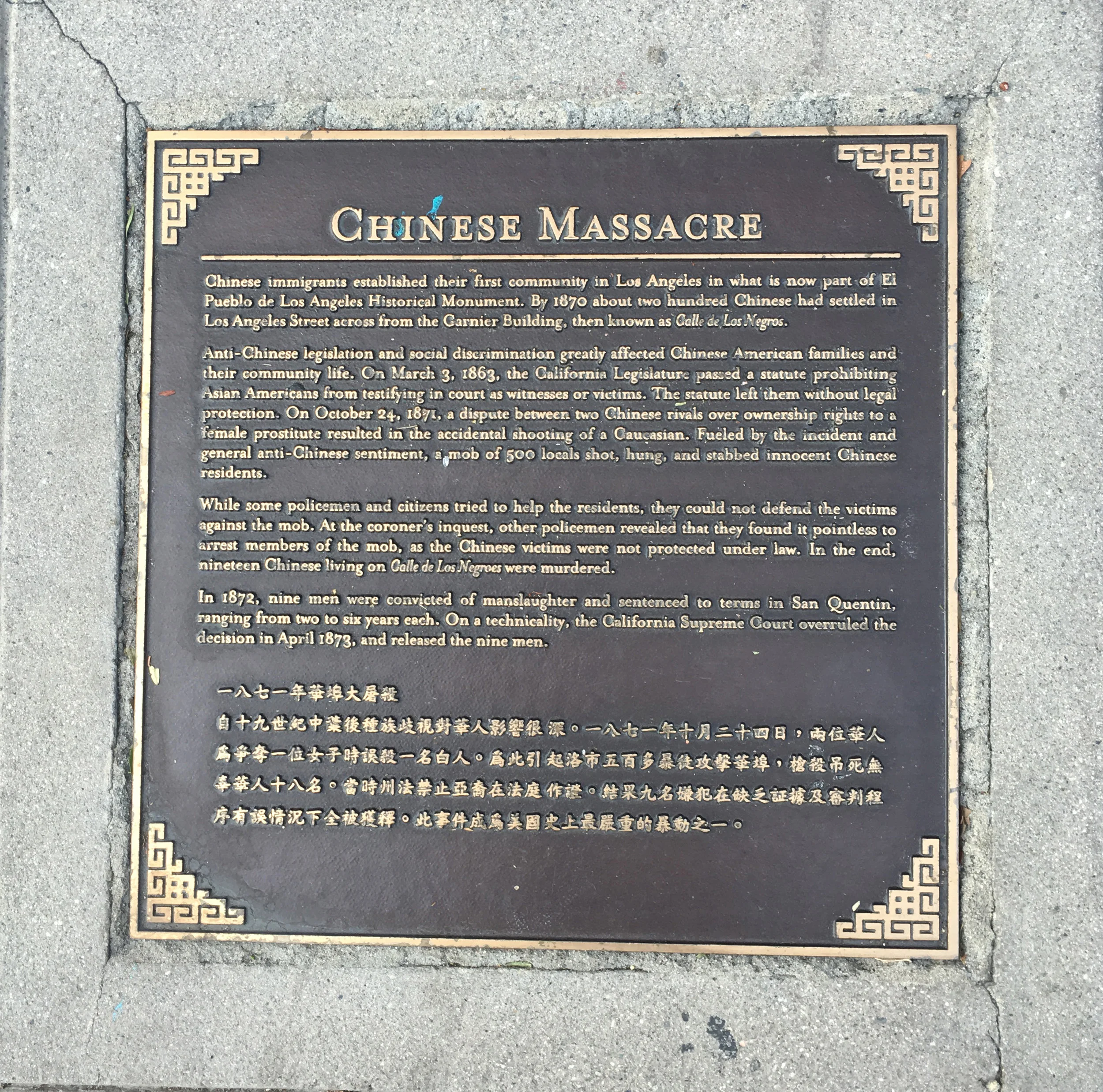

There is a grainy photograph supposedly depicting some of the victims, and a small plaque embedded in a sidewalk off Los Angeles Street facing the Garnier Building, the oldest and last surviving structure of Los Angeles’s original Chinatown.

[a] “. . . a Chinese doctor, an inoffensive man, respected by all the white people who knew him. He pleaded in English and in Spanish, for his life, offering his captors all his wealth . . . but in spite of his entreaties he was hanged; then his money was stolen, and one of his fingers cut off, to obtain the rings he wore.” Historical Society of Southern California, Vol 2, No 2, 1894.

[b] Wikipedia and others claim that the Chinese Massacre is “the largest mass lynching in American history.” As terrible as the Massacre was, this statement is not accurate. To cite three of many examples: 38 Santee Sioux Indians were hanged at Mankato, Minnesota on December 16, 1862; 237 Black sharecroppers were lynched in Arkansas in 1919 after they attempted to unionize; and on September 2, 1885, white miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming murdered 28 Chinese co-workers.